God Told Me (part 2)

Last time I raised the question of whether or not God still speaks to us. I explained that I’ve gone from one extreme to the other, first believing that He does, then believing He does not. Now I am reevaluating the issue with the help of Jim Samra’s book God Told Me.

I should mention that I don’t intend for this series to be an in-depth look at Samra’s book. It just so happened that I came across the book in a very different context at a time when the issue had resurfaced.

Or did it “just so happen”?

A central premise of Samra’s book is that God is deeply involved in our individual lives. He loves us, is sovereign over all creation, and guides us along the way. To this I want to give a hearty “amen.”

If you are in Christ, you have the Holy Spirit—God Himself—within you. Let that sink in for a moment. He is working in you to conform you to the likeness of the Son. You are a temple of God, a place where God dwells. You have the Bible to guide you. You are part of a local church community. God knows you, He loves you, He’s working in you, He has a plan for you, and He guides you.

So far none of this should be controversial. Where things heat up is the question of how God leads you. Do you have to be conscious of it? Does it come in specific moments? Can you miss it? Does God communicate with you here and now?

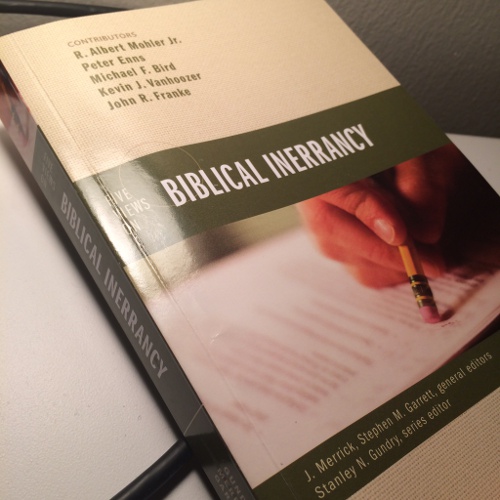

The idea of communication is tricky because now we’re getting into issues of prophecy and the uniqueness of Scripture. As a Protestant, I believe that the Bible is God’s very words, that they carry His authority, that they are without error, that they are complete—not to be added to—and that they are the norm or standard by which everything else should be judged.

But if God still talks to us then those words also carry His authority, they are also without error, and they challenge the idea that the Bible is complete, sufficient for doing God’s will.

And this is the standard criticism: that belief in ongoing revelation undermines the sufficiency of Scripture. My friend Lisa Robinson wrote her master’s thesis on this subject and was kind enough to share a copy with me. She rightly draws attention to 2 Tim. 3:17, which states that the Bible is useful for making the man of God complete, “equipped for every good work,” and to Hebrews 1, which strongly implies that Christ is the consummation of God’s revelation. It would seem that now that Christ has come and the Scriptures are ours, there’s nothing left to say.

So that’s the theological challenge. These biblical doctrines should at very least give us pause when considering that God has more to reveal to us, that we need something more in order to obey Him.

And let’s not miss the point: God can do whatever He wants to do. What’s at issue is not whether God can talk to you. It’s whether or not He would. And if people think He does, is that evidence that He really does, or are they experiencing something like a mirage?

Because here’s the thing: the theological challenge only applies to new verbal communications from God, new words or messages. But when people say “God told me” that’s not usually what they mean. Throughout his book, Samra uses terms like “told,” “spoken,” “heard,” and “say,” but they are all metaphorical. They usually stand in for concepts like “I intuited,” “I felt,” or “I understood”—subjective experiences not linked to a voice or a language or a literal message.

So when Samra says, “God told me who to marry,” he does not mean what the Bible means when God told Abram “I am God Almighty” (Gen 17:1). He means what Laban meant when, after hearing the servant’s story about the LORD’s leading, said “as the LORD has spoken” (Gen 24:51). The servant never described speech, only leading; it was Laban’s interpretation that God metaphorically communicated through those leading actions.

Hopefully this entry has served to help clarify the issues at stake. God is intimately involved in our lives, and there is biblical precedent for using speech terms as a metaphor for God’s leading. Nevertheless, we should be cautious about guarding the Bible’s status as God’s sufficient Word to the church, and about Christ’s status as the pinnacle or consummation of God’s revelation—and thus hesitant to accept new messages claiming to be from God.

To be continued.